why la scarpetta is more political than you think

a story about my grandfather, and what it taught me

Often, we take things for granted that others would give anything for, that our grandparents and ancestors would have given anything for.

I revisited a story a couple of years ago I wrote about my grandfather. It feels even more relevant now than ever, as we face a world engulfed in war, as we watch evil strip others of their land and families.

And, as we see how hope often lies in a single piece of bread.

My grandparents endured that reality. Without his story, I wouldn’t be here. I wouldn’t have this newsletter nor the deep relationship with Italy that keeps my curiosity always hungry.

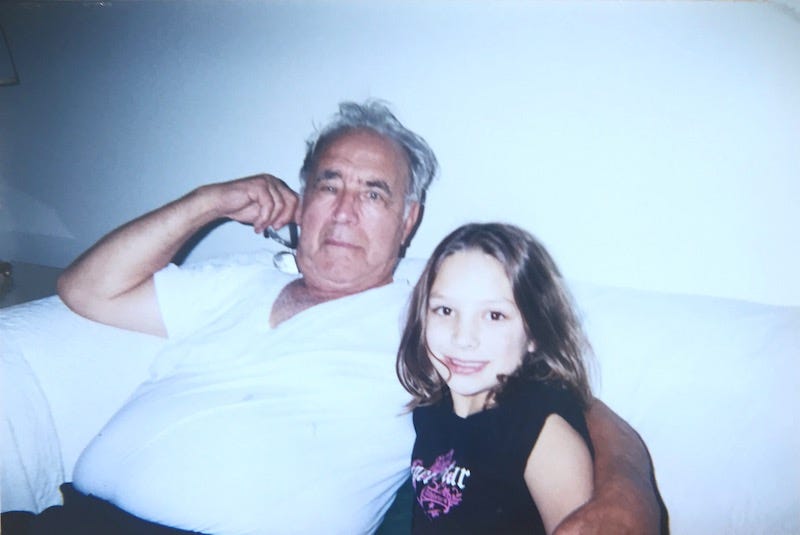

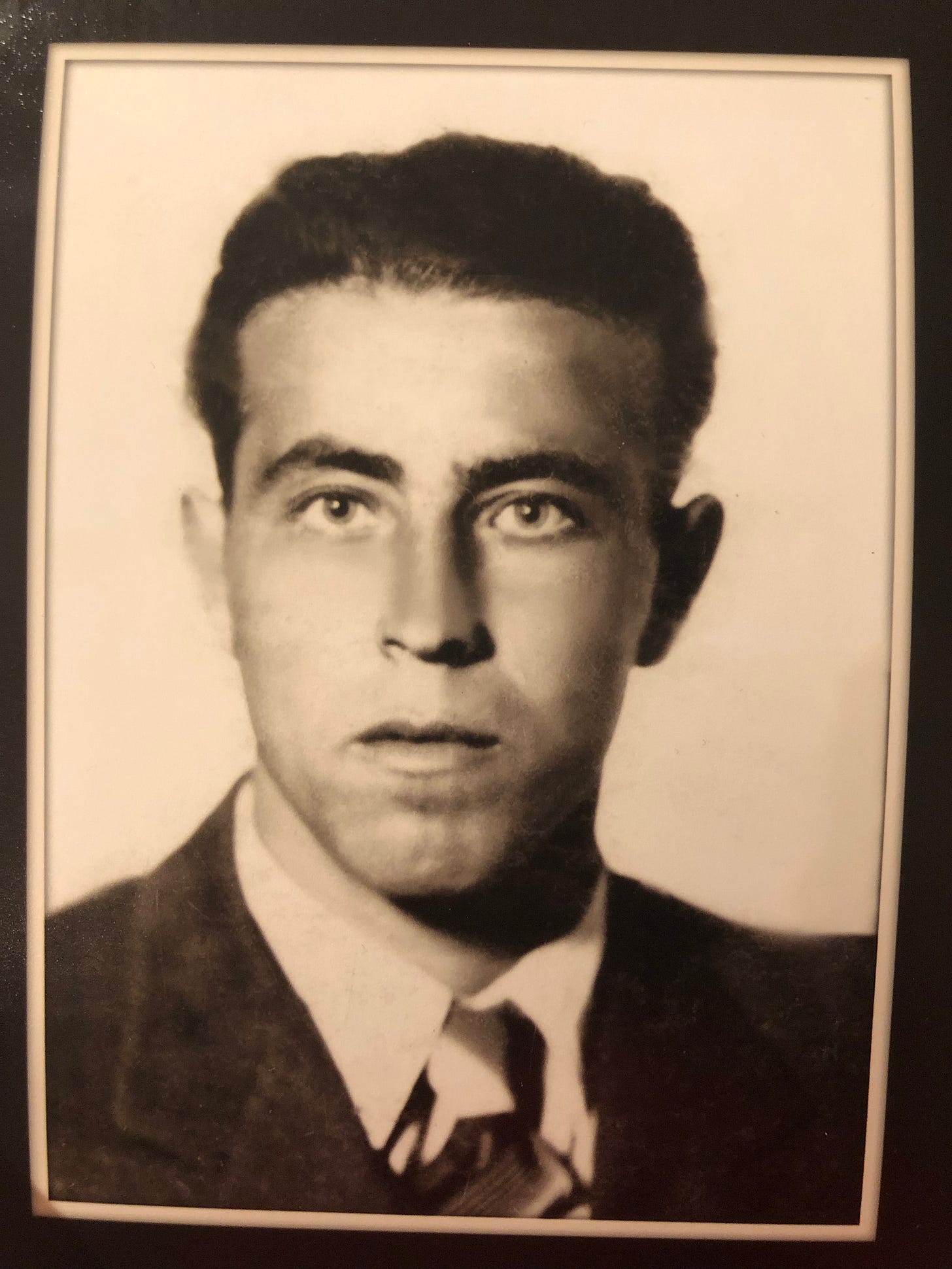

in honor of my grandfather, Arturo Cece

My father told me a story the other day. It was one about my grandfather that I had never heard before.

My grandfather labored in fields before WWII broke out in Basso Lazio, or the southern part of Italy’s Lazio region (where Rome calls home). For lunch, a woman would make a giant pot of maccheroni to feed everyone. It was first-come, first-served. There were a lot of workers.

One day, my grandfather wasn’t as fast to lunch as the other. He knew he was a split second from missing his only meal of the day. He also didn’t have a plate. So what did he do?

He took his boot, jumped over the others, scooped up pasta, and ran.

Now, that may sound gross to some of you. But that’s survival.

This short story completely changed what fare la scarpetta means to me - ‘to do the little shoe,’ aka wiping your pasta bowl clean with a good hunk of bread.

The funny thing is that my family comes from an area named after shoes: Ciociaria. It’s a special cultural region that can’t be located on a map: it comprises the present-day Italian province of Frosinone in the Lazio region. It’s about an hour south of Rome, extending down to the border of Campania.

Ciocie (also known as zampitti) were ancient slipper-like shoes the ciociari people historically wore to scale the hills and mountains. In Rome, slippers are also called ciocie rather than the standard ciabatte.

Ciociaria may sound familiar if you’re a Sophia Loren fan. She won an Academy Award for her performance in Vittoria De Sica’s La Ciociaria, or ‘Two Women’. Based on Alberto Moravia’s novel, this neorealist film is emotionally striking, a heart-wrenching depiction of a mother and daughter’s fight for survival during WWII.

The film is an evocative reminder of how gravely WWII affected Ciociaria during the war. It was in this very region that the battle with the most casualties of WWII in continental Europe occurred: the Battle of Monte Cassino. But that wasn’t the end of the brutality: *movie spoiler* Gourmier soldiers entered the devastated area shortly after, raping and even killing many women - known in Italian history as the marocchinate.

My grandparents endured this very battle, hiding in caves near their homes. The story goes that during this very battle, my grandparents met - a bittersweet reminder that even in the darkest of realities, there can be light.

Still, my grandma rarely spoke about those times; I heard more about the happy moments with her family before the war, selling wine or playing with goats. I did know that during the war, she and her sisters resorted to making shoes out of tires.

Isn’t it beautiful how we’re back to shoes? A necessity for life, just like bread in a way.

In the comfort of our Italian or Italian American homes, we see fare la scarpetta as something cute (how can you resist doing the little shoe? It just sounds so adorable.)

Yet, the significance of la scarpetta is something so much greater -

It's a symbol of survival.

As I scroll on Instagram, jarred by swiping between posts on Roman pasta and people scrambling for bread in Gaza, I can’t help but think about this story. A story that I only heard a few years ago, after a childhood of my father wishing me goodnight with a bedtime story, or should I say anecdote about his big ole crazy Italian family.

Looking back at it, I guess my Dad didn’t want me to know how harsh life could be. He wanted me to see all the good things my grandpa achieved for his family, working 3 jobs to send all his kids to college. And to later sneak a $10 bill to his grandkids at his leisure.

I would always make fun of my Dad for dipping his bread in his wine or OJ. Yes, orange juice.

Or, eating things in the fridge past their prime...only to learn that 'use-by' or 'best-by' dates are just ‘suggestions’, and your senses are the real indicators of safety. And, if he was wrong, there was Brioschi on the shelf just in case.

These were things he learned from my grandfather - observing him at the table, grateful for every single bite of bread, no matter how stale, because nothing goes to waste at the table.

These were things my grandfather learned out of true hardship during WWII, a reality we in the West think only exists in old documentaries and Hollywood blockbusters. But that is far from the case.

Today, bread is more political than ever. We have a hyperglobalized food supply chain, with wheat imported and exported all over the world, more than enough to feed those starving. Yet, bread continues to go to waste on bakery and supermarket shelves as people in more privileged societies opt for low-carb diets; not to mention how corporate food producers have manipulated the mere identity of bread, turning it into some glob of processed gluten that can outlive us all.

I digress, but here’s my point:

Wasting bread, or a single bit of food on our plate, is one of the most political acts we can partake in.

Even in Italy, spaghetti didn’t always grow on trees (as the Brits jokingly advertised in 1957). Italy’s real cuisine is rooted in the farmers, the working class, and the poor who sought to survive. And in turn, created customs and dishes that let them eat something good, and see another sunrise.

With all the glamourizing of Italian cuisine, the world falls into this purist Italian food trap. Sure, la dolce vita is fun, and preserving tradition is important. But the real beauty of Italian food is its foundation in survival, just like shoes and bread.

There’s no doubt that this newsletter dabbles in indulgence. But, I feel it’s time we come together to look at food for its beauty, but also its power.

So I ask you, at home or on your trip to Italy, to be grateful for everything that is on your plate. To enjoy each bite from the start to the scarpetta, for those before and now in the world who wish they could be at the very table you are.

Xx,

Victoria

in memory of:

Arturo Cece

Anna Antonia Cece

Marie Riccardi

Maria Giovanna ‘Aunt Jennie’ Cece

What a great reminder about being grateful for what you have, the artificial scarcity that society (capitalism) creates, and the blessings of family that worked to provide for the future generations. Thank you!

I love this and reading from Genzano, city of bread. My husband's origins are ciociaro on his paternal side, and his family emigrated to Rome and the Castelli Romani post war. His father was sent to a wet nurse in Frosinone or as they say, 'Frosilone.'